Sadly, the myth that television was “too complex” for a single individual to invent persists.

With its September 4, 2017 edition, The New Yorker magazine delivered its first-ever “Television Issue,” featuring articles mostly on said subject. In a preamble to The Television Issue that appeared only on the magazine’s website, How Television Became Art, editors Joshua Rothman and Erin Overbey site an essay by Malcolm Gladwell that first appeared in the pages of The New Yorker back in May of 2002.

Gladwell’s The Televisionary: Big Business and the Myth of the Lone Inventor starts out as an expansive review of two books about Farnsworth that were published in 2002: The Last Lone Inventor, by Evan I. Schwartz and The Boy Genius and the Mogul, by Daniel Stashower (no mention of a third book on the subject also published that year). In the essay/review, Gladwell starts out on the right foot, stating rather unequivocally that “Philo T. Farnsworth was the inventor of television….” but he then discounts the epic nature of Farnsworth’s invention by asserting the obvious observation that raw inventions require refinement: “Everyone was working on television,” Gladwell wrote, “and everyone was reading everyone else’s patent applications, and, because television was such a complex technology, nearly everyone had something new to add.”

Rothman and Overbey reinforce this conclusion when they cite Gladwell, adding: “The truth was that television was an incredibly complex technology; hundreds, even thousands, of engineers had contributed to perfecting it.”

I don’t dispute that television was “a complex technology” and that “hundreds, even thousands” of brilliant minds took a raw invention and made it suitable the commercial marketplace.

But what Gladwell, Rothman and Overbey continue to ignore is that Farnsworth’s contribution was not, as Rothman and Overbey write, “one of the first working television cameras.” It was THE FIRST all electronic television camera, and as such was a breakthrough of epic proportions. The Image Dissector puts a pin in pivotal moment in human evolution that has for too long been uncelebrated – despite the fact that Farnsworth subsequently delivered more than his share of improvements, including the Image Orthicon tube that was the foundation of the broadcast industry in the late 1940s and 1950s.

I have taken it upon myself to send a “Letter to the Editor” of the New Yorker, hoping that it will find its way to Rothman, Overbey, and maybe even Gladwell. I frankly have little hope that my words will find their way into the pages of the august New Yorker, so I post them here:

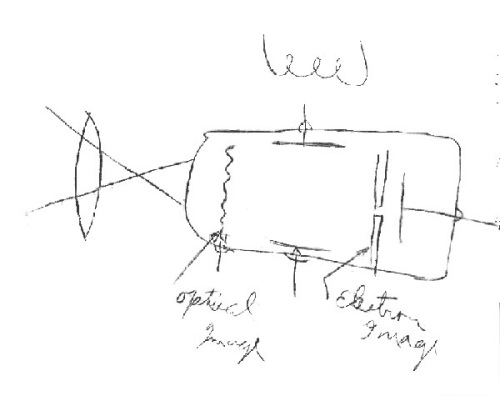

Subject Header: Television, Art – and Seminal GeniusTo the Editor:The online preamble to your recent Television Issue (How TV Became Art by Joshua Rothman and Erin Oberbey; NewYorker.com August 28, 2017) begins with a reference to Malcom Gladwell’s 2002 essay in which he discounted the contribution of Philo T. Farnsworth in the advent of the medium. This dismissal tragically repeats one of the recurring misconceptions of television’s technical origins.In 1922, Farnsworth – then all of 15 years old – drew for his high-school science teacher a sketch of a simple but elegant device, which he would later dub the “Image Dissector.” He built and successfully tested the device for the first time on September 7, 1927.This was not, as Rothman and Oberbey assert, “one of the first working television cameras.” This was the first all electronic television camera.The distinction is not insignificant. Rather, it represents a pivotal moment in the evolution of modern technology, since it abandoned the Newtonian contrivances of the 19th Century for the relativistic physics of the 20th – all in the pursuit of “moving pictures that could fly through the air.”To say that “television was an incredibly complex technology; hundreds, even thousands, of engineers had contributed to perfecting it…” discounts a breakthrough of epic proportions in what mankind could do with quantum forces and particles. Farnsworth was the first to focus and steer electrons in a manner that cleared the path for the most ubiquitous appliance in human history.As I write, we are days away from the 90th anniversary of the arrival of television-as-we-know-it on this planet – an event of historical significance which will be sadly overlooked because of the sort of sentiments expressed first in essay’s like Gladwell’s, and now reiterated by Rothman and Overbey.Farnsworth’s invention made everything that came before it obsolete, and everything that came after it possible. Every video screen on the planet – including the one on which I am typing this message, and the one on which you will no doubt read it – can trace its origins to that sketch (attached below).That sketch demonstrated a measure of genius that is demonstrated only a handful of times in any given century. In this case, it is a forgotten genius that is re-awakened billions of times every day – every time a television is turned on.I hope you’ll share this news with your readers.Thanks,Paul SchatzkinPegram, TNP.S. At least pass this on to Gladwell – he might want to revisit the subject for his podcast, “Revisionist History.”

Thank you for your service in helping to unveil illusions and revealing the true pantheon of the Realm, Mr. Schatzkin.

I only now discovered you on My Family thinks I’m crazy podcast, and will comb everything you have written.

Keep up the great work!

Bill McKinney

Hello Bill. Thank you for tracking me down and the kind words. Glad you liked the podcast.