Have you seen Oppenheimer yet?

As the world braced itself over recent weeks for the cultural shock wave of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, I have been preoccupied by one scene in the trailer.

It’s the scene where Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) meets Albert Einstein (Tom Conti) at the edge of a pond on the grounds of the Institute of Advanced Studies in Princeton, NJ – where the two were colleagues in the final decade of Einstein’s life (he died in 1955).

Einstein’s actual presence as a character in Oppenheimer is limited to a tiny fraction of the film’s three hour run time – but his work in the first decades of the 20th century laid the theoretical foundation for nuclear power and his presence lurks over the entire story.

Einstein is first mentioned about five minutes into the film. He makes his first appearance with Oppenheimer by the pond about five minutes later. There is another scene in the middle of the second hour where Oppenheimer asks Einstein to look at some alarming calculations that have come out of Los Alamos – which scene is recalled in the movie’s final scene – a reprise of the earlier scene by the pond.

I didn’t have Google very far to determine that none of that ever actually happened – which only matters if you care that the denouement of the whole three hours is based on a false premise.

But that’s not what I came here to talk to you about tonight.

Einstein and Oppenheimer

I was interested in how Einstein would be portrayed not just because the bomb’s potential is based on his famous equation E=mc2. My curiosity about Einstein’s presence in the film – and contemporary popular culture in general – derives from recently recalling anew that the whole science of quantum mechanics effectively began with the first paper that Einstein published in 1905. His articulation of the Photoelectric Effect – for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1921 – laid the foundation for all the discoveries in physics over the ensuing three decades that led to the development of nuclear weapons.

You know what else came out of the Photoelectric Effect? You’re looking at it: electronic video.

More than a dozen of the leading lights of mid-20th-century physics gets at least a cameo in Oppenheimer: Neils Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Hans Bethe, Ernest Lawrence, Leo Szilard, Richard Feyman… You really need a program to tell all the players.

You know who was the most renowned scientist of the era who did not work on The Manhattan Project?

That would be Philo T. Farnsworth, the guy who turned Einstein’s Photoelectric Effect into electronic video – the most ubiquitous appliance in the history of appliances.

Farnsworth’s knowledge of – and disinterest in – The Manhattan Project is addressed in The Boy Who Invented Television:

Chapter 16 – False Dawn:

Not long after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Farnsworth received a visit from Dr. David Webster, a professor of physics at Stanford University who flew his own small airplane in short hops all the way across the country to Maine with an intriguing, mysterious offer. Dr. Webster wanted Phil to join an important “government research project” in Chicago. When Phil tried to learn more about the project, his visitor refused to say any more. The project was top secret. But Phil had his suspicions.

“I think they’re trying to build an atomic bomb,” Phil confided to Pem, “but I don’t want anything to do with it.”

Chapter 16 goes further into a scene depicted in Oppenheimer:

The project that Webster tried to recruit Farnsworth for turned out to be Enrico Fermi’s first “atomic pile.” On December 2, 1942, the Italian physicist Fermi and his team, working in a converted squash court beneath the bleachers of a football stadium in Chicago, succeeded in achieving the first controlled release of the energy that Albert Einstein had long predicted would be found binding the nuclei of atoms. Fermi’s Chicago Pile turned out to be an important breakthrough on the path that only three years later would deliver the first atomic bombs.

While the diaspora of quantum physicists – many of them Jews forced to flee Europe when Hitler crawled out of his swamp – reassembled on Oppenheimer’s mesa in New Mexico, Farnsworth was exploring his own parallel path from the woods of Maine:

Farnsworth could not have known precisely what Dr. Webster was proposing, nor what Fermi was working on in Chicago. But it is clear that Farnsworth’s creative processes were taking him down a similar path, as he contemplated his own ideas about how the energy that Einstein discovered might be released from atomic nuclei.

Farnsworth didn’t sit out the war entirely. From his retreat in Maine he formed a company tp harvest timber and mill boxes for bullets that were shipped overseas. He was quite comfortable making boxes for bullets, but he would have nothing to do with using his special knowledge to forge a weapon that could vaporize entire cities.

While the team at Los Alamos was focused mostly on fission – splitting atoms –Farnsworth was already thinking about fusion – squeezing atoms together. Much like Einstein after the war, Farnsworth was interested in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. That mutual interest eventually caused their paths to cross in…

Chapter 17 – It’s My Baby.

As intrigued as he was at the prospect of supplying the world with a boundless source of electrical energy, he was equally obsessed with the notion that such a discovery would reveal marvels that he was beginning to believe about the inner and outer workings of Einstein’s universe. He was also certain that fusion would provide an efficient means for traveling in outer space.

This was an immense, convoluted corridor that was carving its way through the gray matter of Philo Farnsworth in the 1940s. This time, however, there was no… benevolent tutor he could spend afternoons with, drawing sketches on chalkboards and doodling diagrams in sketch pads. Absent a reasonable sounding board, at least one corner of his brain had to keep a watchful eye on his sanity.

All that changed one afternoon in the summer of 1948, when Phil and Pem were in New York for a board meeting. They visited the home of Frank Reiber, a friend from their San Francisco days. Phil was surprised to find the Reibers’ apartment adorned by a portrait of Albert Einstein that had been painted by Reiber’s mother—quite possibly the only time Einstein had ever agreed to sit still long enough to have his picture painted.

Admiring the painting, Farnsworth shared a secret desire with his friend. “You know, I’d love to talk to Einstein some day about some of these ideas I’ve been thinking about. But I really need to get some of my math together before I can do that.”

Reiber had a better idea. “Why wait?” he said. “Let me see if I can get Einstein on the phone for you.”

Einstein and Farnsworth

Reiber disappeared into the bedroom, and reappeared a few minutes later saying, “I’ve got Einstein on the phone, and he’d be delighted to talk to you.”

Nearly an hour later Phil emerged from the bedroom, “his face aglow from the excitement of finding someone who knew what he was talking about.”

At the time of this conversation Albert Einstein —self-exiled from Nazi Germany and a lifelong pacifist— was disturbed after his theories were applied to flatten Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But when Farnsworth told him the direction his thinking was taking him, Einstein told Phil that he, too, had been thinking along similar lines.

When Phil told Einstein that he had some rudimentary ideas about how to harness the power of fusion, Einstein is reported to have replied,

“You must continue this work. This is the good part of my theories.”

When Farnsworth left Frank Reiber’s apartment that day, he was greatly encouraged that his own ideas were sound, and more determined than ever to follow the path he was on to some kind of fruition. He had also promised Einstein that he would publish his math as soon as he could get it a bit more formalized and suitable for publication.

The Mystery Persists

Why Farnsworth never fulfilled his promise to Einstein, why his fusion patents are incomplete – these are the mysteries that connected Einstein and Farnsworth – however momentarily – in the mostly forgotten annals of science history.

But we will always have Oppenheimer.

It seems that the forces of cultural capitalism can round up $100-million to produce a movie about blowing shit up.

But use the most powerful story telling medium in the history of story telling to tell the story of its own origins?

Eh… not so much.

That’s humans for you.

We are frequently reminded in the most compelling ways of the looming threat of mushroom clouds, but take entirely for granted the benign genius that is reawakened every time we turn on our giant flat panel display – or whip a gizmo out of our pocket.

Is it any wonder we can’t have nice things?

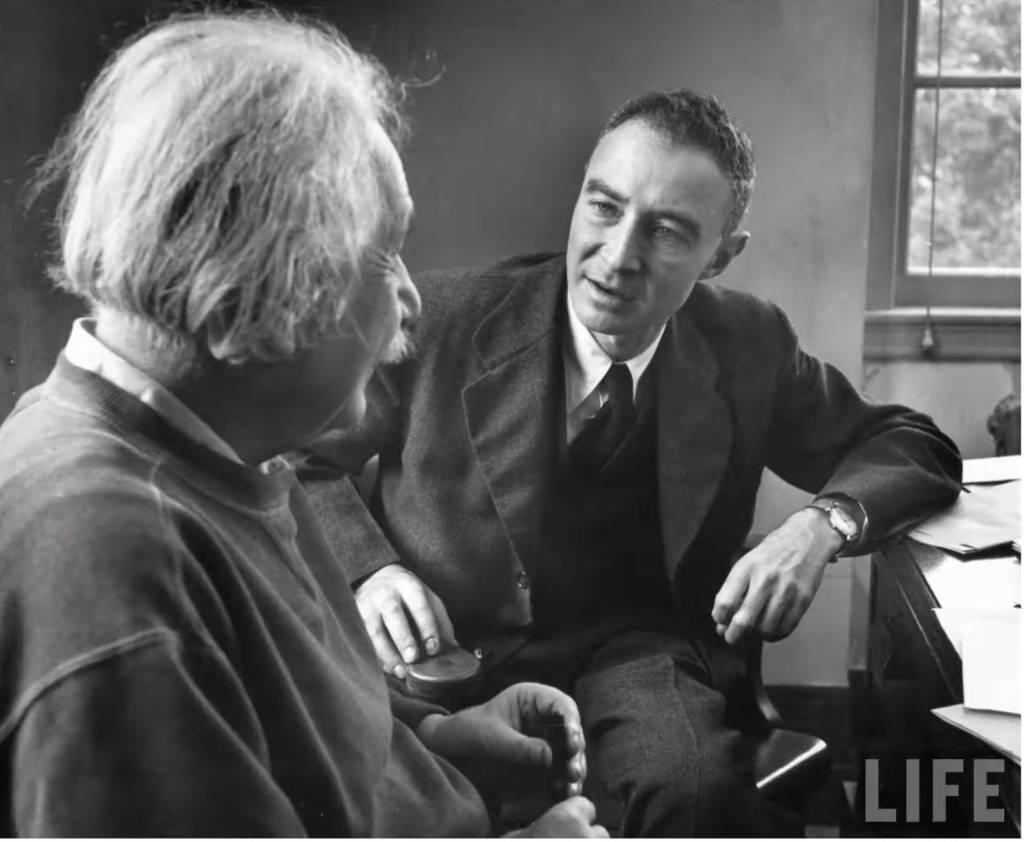

Einstein and Oppenheimer at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton NJ ca 1952.

Enjoyed this post and had some good background. While an atomic bomb would have existed whether the war caused it or not (though the time frame would have been far different), I’ll pass on further comments on that topic.

To say Farnsworth didn’t fulfill his promise to Einstein is a bit harsh; that would have been impossible (in hindsight now) but he certainly tried and while going up the wrong tree, one cannot blame him since no one to this day has climbed the correct tree so far. Ironic if the Germans with Wendelstein 7 (the best Stellarator to date) manage to demonstrated the machine design most likely to accomplish that task.

Is there any remote chance that nuclear weapons proliferation has been greatly exaggerated to keep humans in ptsd mode, that even 1945 was just monster amounts of tnt?

Well, I suppose there’s always that chance, things do seem to work that way sometimes. Still it’s hard to imagine how nations having even a handful of thermonukes in their arsenal wouldn’t be a source of concern. Are you suggesting that the actual professed numbers of warheads – in the multiple thousands on either side – is overstated. I guess that would actually comforting, if annoying. Still, there is certainly at least that handful.