Who Invented Television?

To have the right idea is one thing.

To have the right idea and make it work is everything.

–– Roger Penrose

__________________

As compelling as the story of Philo T. Farnsworth may be, the historical record regarding “who invented television” remains fuzzy at best, deliberately distorted at worst. The debate often comes down to a simple question: Does any single individual deserve to be remembered as the sole inventor of television? Can we create for television the kind of mythology of individual, creative genius that history has bestowed on Morse, Edison, Bell, or the Wright Brothers?

In The Beginning…

The question may be simple, but clearly the answer is not. Before Uncle Milty, before Walter Cronkite, before Lucy and Desi and Ethel and Fred, before Archie and Edith and Charlie’s Angels, before the Sopranos or the Baratheons or the Lannisters or the Targaryans, literally hundreds of scientists and engineers contributed to the development of the appliance that now dominates “our living room dreams.”

How can we single out any single individual and say, “it all started here”?

The historical record is mostly devoid of references to Farnsworth. Though the oversight has begun to improve in recent years, it is still entirely possible to read that electronic television began when “Vladimir Zworykin invented the Iconoscope for RCA in 1923”—a sentence that manages to contain no less than three historical inaccuracies. The most conspicuous error—the “1923” date—fixes Zworykin’s name chronologically before Farnsworth’s 1927 patent filing, and often renders Farnsworth to the status of “another contributor” in the field.

Some historians have gone so far as to suggest that Farnsworth and Zworykin should be regarded as “co-inventors.” But that conclusion ignores Zworykin’s 1930 visit to Farnsworth’s lab, where many witnesses heard Zworykin say, “I wish that I might have invented it.” Moreover, it ignores the conclusion of the patent office, in its 1935 decision in Interference #64,027, which states unequivocally that “priority of invention is awarded to Farnsworth.”

These misreadings of the historical record are precisely what eighty years of corporate public relations wants us to believe—that television was “too complex” to be invented by a single individual.

But close examination of the stories beneath the written record reveals a far more compelling story: In fact, there was one inventor of electronic television. Video as we now know it first took root in the mind of Philo T. Farnsworth when he was fourteen years old, and he was the first to successfully demonstrate the principle, in his makeshift laboratory in San Francisco on September 7, 1927. If you want to fix a date when video arrived on the planet, that’s the date.

Before that date, television was the province of Newtonian electro-mechanical engineers who employed spinning disks and mirrors in their crude attempts to scan, transmit, and reassemble a moving image. The inventions of Jenkins, Ives, Alexanderson, Baird, and others are all similar in their reliance on the spiral-perforated, spinning disk first proposed in the 1880s by the German Paul Nipkow. These 19th century contraptions were engineering marvels in their own quaint way, but they were not the sort of 20thcentury breakthrough that real television required.

On September 7, 1927, Philo T. Farnsworth demonstrated for the first time that it was possible to transmit an “electrical image” without the use of any mechanical contrivances whatsoever. In one of the very first triumphs of Albert Einstein’s cosmology, Farnsworth replaced the spinning disks and mirrors with the electron itself, an object so small and light that it could be deflected back and forth within a vacuum tube tens of thousands of times per second. Farnsworth was the first to focus and manipulate an electron beam, and that accomplishment represents an epic breakthrough in what humans can do with quantum particles and forces.

After September 7, 1927, every new contribution to the art—including Zworykin’s—was an improvement on Farnsworth’s simple, elegant, and profound invention.

What About Zworykin?

What is too often overlooked cannot be overstated.

In 1923, Vladimir Zworykin—recently emigrated from Russia, and employed at the time by the Westinghouse Corporation in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—applied for a patent for an approach to television. That application reflected ideas that he first encountered in the classroom of Boris Rosing, his former teacher in Russia.

In 1927, Philo Farnsworth also applied for a patent. Later that same year, Farnsworth produced the first successful transmission of a television image by wholly electronic means—an event that is thoroughly documented in Farnsworth’s journals—while Zworykin’s application was still pending. Farnsworth’s patent, #1,773,980—with the critical Claim 15 disclosing the “electrical image”—was issued in August 1930—and Zworykin’s application was still pending.

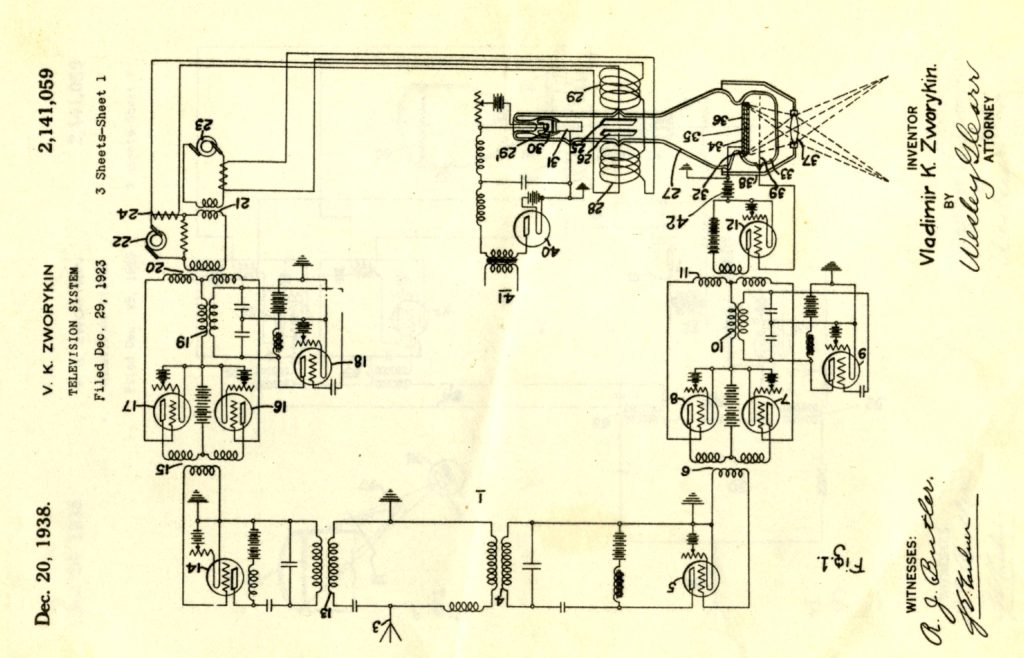

Zworykin’s 1923 application would be entirely forgotten—except that a patent for the Iconoscope was finally issued in 1938 bearing the 1923 application date. This patent (#2,141,059) was issued an extraordinary fifteen years after the application date, and then only after extensive revisions had been made to the original application.

Furthermore, the eventual patent bearing the 1923 application date was issued over the objection of the patent office, and even then, not until the case was adjudicated by a civil court of appeals. That this Iconoscope patent was issued at all hinged on a technicality, and it served no practical purpose other than substantiating the dates that RCA would eventually use in its public relations.

RCA’s obtaining this patent in 1938 has served as the cornerstone of its efforts to influence the historical record, since the patent effectively fixes 1923 as the date that Zworykin first disclosed his erstwhile invention. Decades later, historians and scholars are still including this dubious 1923 date in their chronologies.

What’s wrong with the Zworykin patent? What’s wrong is that the original application—the system that Zworykin disclosed in 1923—simply could not work. The idea was on the right track, but the application fell far short of disclosing a device that would pave the way to electronic video and ultimately put a television in every living room or a computer monitor on every desktop.

There is scant evidence that Zworykin ever built and tested a system like the one disclosed in his 1923 application. One story does exist about Zworykin’s attempt to demonstrate his concept for executives at Westinghouse, where he was employed at the time, in hopes of obtaining more funding for his research. The demonstration was so dismal that instead of providing him with further funding, Zworykin’s superiors ordered him to “find something more useful” to work on.

The usual retelling of this story is cast in such a way that we are supposed to believe that the Westinghouse executives who witnessed this demonstration were too shortsighted to appreciate its promise.[i] It seems more plausible to conclude that what they saw showed little promise because it simply did not work. Some historians suggest that witnesses observed some sort of blurry smudge. Zworykin would claim years later that the image of a cross was transmitted. But in the critical 1934 interference proceedings there was no evidence submitted to support even these modest contentions.

Zworykin’s debatable patent history is often traced to The History of Television: 1884 – 1941 by Albert Abramson.[ii] A careful examination of Abramson’s book only serves to further illustrate the flimsiness of the account. The evidence that such a demonstration ever took place is sketchy at best, considering its potential historical significance. There are no lab notes or direct eyewitness testimony. There are only Zworykin’s own accounts, and a single document on page 80 of Abramson’s book that he claims to have found buried in some archives fifty years after the purported event. This document describes a device “using a modified Braun type cathode ray tube for transmitter and receiver …the receiving tube …gave quite satisfactory results …[but] the transmitting part of the scheme caused more difficulties ….”[iii]

That’s it; that’s all it says about the camera tube, that it “caused more difficulties.” It’s hard to imagine how the receiver could be “quite satisfactory” if the camera was not equally satisfactory, but this is the document that compels Abramson to conclude—in his footnotes, no less—that “Zworykin did build and operate the first camera tubes in the world sometime between the middle of 1924 and late 1925.”[iv] This is the feeble foundation on which historians RCA’s claim that Zworykin should be regarded as the “inventor of television.”

Zworykin may indeed have built some tubes. And he may have applied current to them. But it should take more than a statement that “the transmitter caused more difficulties” to convince students of history that he successfully “operated” such a device prior to September 7, 1927, or that Zworykin deserves to be considered even a “co-inventor” as a result of this dubious account.

Patent Litigation

Serious students of this history should look no further than the decision of the U.S. Patent Office in its 1935 ruling in Interference #64,027. This is the litigation in which Farnsworth successfully defended Claim 15 in his patent #1,773,980, which describes the “electrical image.”

It’s worth reading this brief passage in its entirety:

An apparatus for television which comprises a means for forming an electrical image, and means for scanning each elementary area of the electrical image, and means for producing a train of electrical energy in accordance with the intensity of the elementary area of the electrical image being scanned.

That wording announces the arrival of electronic video on the planet.

There is no way to make, send, or receive a television signal without doing what that paragraph says. You can’t create an electronic television signal without first creating an “electrical image.”

The whole of RCA’s research effort—at an expense that David Sarnoff joked with Zworykin years later cost RCA more than $50 million—was intended to circumvent Farnsworth’s patents, in particular Claim 15. The language in Claim 15 was indispensable. RCA’s attorneys went to great lengths to assert that Zworykin’s 1923 application would have created such an electrical image, and that Zworykin was therefore entitled to “make the count” embodied in the Claim.

That’s when RCA should have produced some… what’s it called? Oh yeah… evidence. But when it was time for RCA to prove that Zworykin had constructed and operated his system in 1923 – or 1924 or 1925 – there was no evidence submitted. No tubes were displayed, no laboratory journals entered into the record. There were only confusing and contradictory verbal accounts from Zworykin and two of his colleagues.

After considering all the testimony, the patent office ruled unequivocally that “Zworykin has no right to make the count.”[v]

The patent examiners were unequivocal in their decision: ‘Priority of invention is awarded to… Philo T. Farnsworth’ .

The case was appealed and RCA lost all the appeals. This pattern went on, over this and other patents, until RCA capitulated in 1939 and accepted a license from Farnsworth for the use of his patents—the first such license in the history of a company that was determined to “collect patent royalties, not pay them.”

Yet here we are many decades later, still debating the merits of a patent that was awarded by a court of appeals in 1938 that validated a patent application from 1923 that was ruled inoperative in 1934.

Prevailing Contradictions

A more discerning examination of the record reveals that Zworykin believed in electronic television but was still struggling for a viable solution until he visited Farnsworth’s lab in 1930. As soon as he saw what Farnsworth had achieved, he got busy, duplicating Farnsworth’s equipment at the Westinghouse lab in Pittsburgh before moving on to RCA in Camden. He then built on Farnsworth’s work, as well as the work of other contributors, to produce the Iconoscope.

Zworykin’s corporate benefactor, David Sarnoff, believed the Iconoscope gave him the leverage he needed to bring RCA’s legal hammer down on Farnsworth and commandeer his patents. Sarnoff ultimately failed in that effort, and RCA was left with no choice but to accept a patent license from Farnsworth. Still, we read time and again that Zworykin made modern television possible when he “invented the Iconoscope for RCA in 1923.” The facts are that Zworykin was not working for RCA in 1923, the Iconoscope did not exist at that time, and it is questionable whether Zworykin truly invented it at all.

Zworykin got some momentum going in the mid-1930s with the Iconoscope, but it was not until the Image Orthicon was introduced that the industry had the tool it really needed to bring the world into our living rooms. But even the Image Orthicon—originally thought to be an RCA development—was in fact descended from Farnsworth’s patent #2,087,683, which was the first to disclose a low velocity method of electron scanning. This lends further strength to the conclusion that everything that came after September 7, 1927, was an improvement on the concept proven that day—including Farnsworth’s own subsequent inventions.

There is no question that much credit for refining many aspects of television technology goes to RCA engineers. There were hundreds, maybe thousands, of individuals who contributed to the development of electronic video before TV broadcasting reached the general public in the 1950s. Thousands more have contributed to its advancement in the decades since. But refinement is not invention––certainly not the sort of quantum leap that the pivot from mechanical to electronic video represented in the 1920s.

Who Cares?

Why is any of this important? A century later, who really cares who invented television? What difference does it make whether electronic television was first developed by a Russian émigré or a Mormon farm boy?

It matters because the suppression of the true story deprives us of some important insight into the human experience. It tempts us to believe that progress is the product of institutions, not individuals. It tempts us to place our faith in those institutions, rather than in ourselves.

Invention is one of the most unique and compelling aspects of human evolution. From the moment the first ape picked up a bone and swung it like a club, the history of civilization has followed the path of invention.

Szent-Gyorgyi put it best when he said, “Discovery is seeing what everybody else has seen, but thinking what nobody else has thought.” Therein lies the operative definition of genius.

In Zworykin, we find a capable engineer, one who could see what others were doing and improve upon it.

But in Farnsworth, we encounter the rarest breed of all, the true visionary who could see the obvious—and think up something entirely different. Obscuring his story and denying his contribution deprives us of our understanding of this critically important facet of the human character.

Television is our blessing and our curse. The ancient dream of a unified planet came true with the moonwalk in 1969, as hundreds of millions of people around the world tuned in to witness the event through the medium of Philo T. Farnsworth’s divine inspiration. At the other extreme there are the routine daily programs that cater to “the lowest common denominators” of our society. But even these daily panderings are somehow elevated when reconsidered with the knowledge that the medium itself is a consequence of individual genius rather than corporate engineering.

The belief that video—the most pervasive communications system of the past millennium, and perhaps the next—was “too complex to be invented by a single individual” deprives us of the knowledge of the noble individual whose unique gifts made it all possible. There are only a few such souls in each century, men like Tesla, Armstrong, and Einstein whose lives are an enduring expression of Szent-Gyorgyi’s axiom.

Philo T. Farnsworth was as noble a spirit as has ever graced this planet. From the first declaration of his hope that he had been “born an inventor” it is clear that this earthly soul was an instrument of providence.

When he saw how the mad scientists of the 19th century tried to send pictures through the air with spinning disks and mirrors, he alone replaced all the moving parts with the invisible electron. Recalling that contribution makes even the most ordinary moments of television programming an expression of divine inspiration.

______

[i] Fisher and Fisher, pp 136-137.

[ii] Albert Abramson, The History of Television, 1880 to 1941; 1987, McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC.

[iii] Ibid., p. 80.

[iv] Ibid., p. 287.

[v] United States Patent Office; Patent Interference No. 64027—Farnsworth v. Zworykin—Television System. Final Hearing April 24, 1924, decision rendered July 20, 1935. The reference to “discrete globules” refers to a distinguishing feature of the Iconoscope, which Zworykin was testing in the mid-thirties. Since the decision says that the 1923 application did not disclose such globules, the decision further reinforces that the 1923 application was not the Iconoscope.