Part 11: "Tears in His Eyes"

by Paul Schatzkin

Prologue to the Conclusion:

Sometime in 1927....

One night, going home on the ferry, Phil led me out on the deserted

back deck. The sky was clear for San Francisco, and the stars

were brilliant. Phil put an arm around me as shelter from the

everpresent wind. Looking skyward, he asked if I thought

there was life out there.

"I haven't thought much about it," I confessed.

"Don't you think it pretty egotistical to think that we,

on this tiny planet we call Earth, are the only intelligent creatures

in this immense universe?"

"Now that I think about it, I guess it is."

"I think there are beings out there who have far surpassed

us in development, mentally and otherwise. I intend to take an

expedition out there some day and find them."

"That sounds very ambitious to me."

"It is ambitious. We would need a carefully picked group

of people, hopefully couples, each well trained in some phase

of science or medicine. The spaceship would have to be large enough

to be entirely selfsufficient. We would take animals for

food and grow our own vegetables in hydroponic gardens, because

we would be gone for a very long time. In fact, it might be up

to our children or even our grandchildren to bring the ship back."

"You keep saying "we"; I hope you aren't

expecting me to go along."

"I had hoped you would. I hate to think of going anywhere

without you." I was glad he felt that way. Certainly,

if he left this earth, I didn't want to be left behind.

"I get goose bumps just thinking about it, but when it comes

right down to it, I'd rather die with you in space than live on

earth without you."

"That's my girl. I knew I could count on you. Anyway, we

have much to do before we could take on such a project-it may

take longer than we think to get television to the commercial

stage."

"Trust you to think big."

from Distant Vision: Romance and Discovery on the Invisible Frontier

by Elma G. (Pem) Farnsworth

And now.... the conclusion...

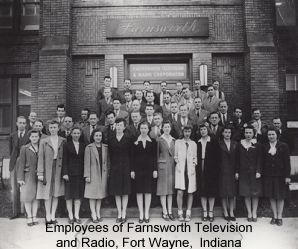

It took nearly two years to hammer out the details of the deal

that would put Farnsworth in the electronics manufacturing business.

George Everson and other officers of the company spent most of

that time in New York, working closely with Kuhn, Loeb, and other

Wall Street contacts, while Philo monitored the progress from

the lab in Philadeiphia, where he had picked up the new work that

preoccupied him when the lab gang was fired.

The deal began to take shape when Kuhn, Loeb learned of a plant

in Fort Wayne, Indiana, that was being sold as part of the liquidation

of the Capehart Company, once regarded as the most elegant name

in automatic record changers and jukeboxes. The company slid into

bankruptcy when one of its most expensive mechanisms developed

a habit of breaking the records it was supposed to change.

Once Capehart's creditors accepted the Farnsworth offer, other

components of the deal began to fall into place, and new faces

began to play an increasingly important role in Farnsworth's life.

Curiously enough, many of the men who joined Farnsworth as executives

of the new company were defectors from RCA. For men like E. A.

Nicholas, who left a lucrative post as a marketing manager with

RCA to accept the position of president in the new company, the

move provided opportunities that could never exist at RCA so long

as David Sarnoff remained in command.

Though the move presented obvious risks, Nicholas felt that they

were justified, since working with Farnsworth presented him with

a chance to build from the ground up an enterprise that could

conceivably rival his former employer.

As much as ironing out the business affairs of his company was now the province

of financiers, so too the remaining technical chores were the province of

engineers and product designers. As an inventor, Farnsworth thrived on the

more rarefied atmosphere of conceptual research, where an invention is not

so much an end in itself as a way of proving something, in order to advance

the theoretical base of scientific knowledge.

As much as ironing out the business affairs of his company was now the province

of financiers, so too the remaining technical chores were the province of

engineers and product designers. As an inventor, Farnsworth thrived on the

more rarefied atmosphere of conceptual research, where an invention is not

so much an end in itself as a way of proving something, in order to advance

the theoretical base of scientific knowledge.

At the laboratory, Farnsworth engaged himself in taking a mental

inventory of all the work he was doing in hopes of resuming where

he left off, once things were rolling in Fort Wayne. In the meantime,

he spent a good deal of time with Pem and Cliff and his wife,

Lola, trout fishing in streams from the Carolinas to Maine.

Both Cliff and Pem felt that Phil needed the rest, for he had

never fully regained his health since the debilitating days after

his second trip to Europe in 1936. He never seemed to exhibit

quite the same vitality of years before, and especially since

the firing, he was tense and edgy and found it quite difficult

to relax. Forever the man possessed by his work, Phil was reticent

about spending so much of his time on the end of a fish pole.

Still, with the realization that there was not much to do until

the lab was set up in Fort Wayne he decided to take off and spend

sometime with his wife and family. To his pleasant surprise, he

found that fishing put him in just the right frame of mind for

the time, and presented an unhampered opportunity to reflect at

length on what had transpired during his many years in the field

of science.

It was during these fishing trips in 193839 that Farnsworth

began seriously thinking about what should come next. After nearly

10 years of devotion to a single pursuit, his internal compass

seemed to tell him that it was time to do something different.

After one of their fishing trips in the northern reaches of the

Appalachian Trail, Phil and Pem stopped in Brownsville, Maine

to look in on a property that George Everson had acquired in a

foreclosure deal during the depression. The house was a little

run down, but Phil became instantly captivated by the place and

wasted no time burning up the wires to San Francisco, asking George

to sell enough of his stock so that he could buy the 80 acre farm.

In the ensuing months, the Farnsworths returned to Maine several

times, and Phil began devising big plans for the place. In the

back of his mind, he began building the nest in which he would

begin the next phase of his life.

All the contracts and notes that would finalize the plans first

outlined in Farnsworth's living room were ready to be ratified

in March 1939, and comprised, in George Everson's words, "a

volume somewhat thicker than the New York telephone directory."

Among other things the papers included provisions for floating

$3,000,000 worth of Farnsworth stock for the purchase of the Capehart

facilities and for initial operating capital for the new corporation.

The papers were held in abeyance for weeks, while 'he Wall Street

people waited for weak market conditions to subside before floating

their issue. When the market stiffened, March 31 was set as the

closing date. In the final moments before closing, everyone involved

knew that the slightest last minute failure could bring the carefully

planned deal toppling down on them. When the documents were all

signed, George was handed a check for $3,000,000, and the Farnsworth

Television and Radio Corporation was open for business.

The following day Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia.

Phil and Pem stayed in Maine while the Philadelphia lab was crated

and hauled to Indiana. Meanwhile, new pages in the history of

television were written every day, and public interest in the

imminent arrival of the new medium continued to intensify.

The 1939 World's Fair

In a display that was designed both to capitalize on the public's

curiosity and lend historical credence to the event, David Sarnoff

arrived at the opening of the New York World's Fair on April 30,

1939. His entourage included Franklin D. Roosevelt, who became

the first President of the United States to appear on television

in a ceremony staged especially for the benefit of RCA's television

cameras.

In his opening remarks, Sarnoff announced the opening of an epoch: "Now

we add sight to sound," he proclaimed, though there was no mention of

any of the individuals who were directly responsible for that accomplishment.

The event was televised to an audience on the fairgrounds, and was broadcast

to a handful of receivers in the New York area.

In his opening remarks, Sarnoff announced the opening of an epoch: "Now

we add sight to sound," he proclaimed, though there was no mention of

any of the individuals who were directly responsible for that accomplishment.

The event was televised to an audience on the fairgrounds, and was broadcast

to a handful of receivers in the New York area.

Later that week, television receivers went on sale in limited

quantities at a few department stores in New York. These first

commercial sets used the 441 line/30 frame standard proposed to

the FCC by the Radio Manufacturers Association, a group that numbered

virtually ail major contenders in the marketplace. Other companies

announced that they would soon be selling receivers as well. The

industry was anxious to follow RCA's plunge. ignoring the FCC's

delay on formalization of signal standards, they also overlooked

the FCC's denial of licenses for anything other than the experimental

use of television.

Not even the mighty RCA had permission to sell commercial time

to advertisers to support television broadcasting. Sarnoff wanted

the World's Fair opening to go down in history as the arrival

date for commercial television. Knowledgeable observers regarded

the event in more sanguine terms: rather than opening the market

for commercial television, the event only signaled the beginning

of another phase of experimentation, one in which the public would

be allowed to participate through the availability of a handful

of receivers. Television's commercial payoff was still years away.

Fortune Magazine published a broad assessment of television

to coincide with the Fair opening, which described the new medium

as Sarnoff's "Thirteen Million Dollari "IF."

Meanwhile, RCA and Farnsworth were still at loggerheads in their

negotiations for a patent license that would permit RCA to put

its market power behind Philo's invention. RCA had already conceded

that it was not possible to produce electronic video without employing

techniques that were covered by Farnsworth's patents. That portfolio

included all phases of electronic scanning and synchronization,

electrostatic and magnetic focusing, electron multiplication,

the saw-tooth wave, blacker-thanblack horizontal blanking-in

short, all the fundamentals of manipulating electrons to send

pictures through the air. By 1939 Farnsworth had obtained more

than 100 patents. But RCA was still unwilling to pay Farnsworth

a continuing royalty for the use of his patents.

The negotiations bogged down when RCA proposed a clever variation

of its nowfamiliar trading philosophy. Instead of paying

a continuing royalty, RCA proposed to pay all the royalties in

advance, and then proceeded to insist on a rather meager figure-something

in the low six figures. Farnsworth's lawyers flatly rejected the

proposal and sent RCA back to the drawing boards.

Shortly after the opening of the World's Fair, Philo and his family moved

to Indiana where he assumed his position as Vice President and Director of

Research for Farnsworth Television and Radio Corporation. Despite his own

misgivings about assuming such a role, Farnsworth became actively involved

in assembly line engineering and product design.

Shortly after the opening of the World's Fair, Philo and his family moved

to Indiana where he assumed his position as Vice President and Director of

Research for Farnsworth Television and Radio Corporation. Despite his own

misgivings about assuming such a role, Farnsworth became actively involved

in assembly line engineering and product design.

It wasn't long, however, before his mind went back to the subjects

with which he was preoccupied earlier. Once again his mind ventured

toward the unknown. Product engineering became tedious and boring,

but he considered it part of his personal obligation to finish

what he had started. So he spent most of his days working with

engineers at the plant, and his evenings working over the ideas

and equations that had always been his primary interest.

The final chapter

The final chapter in the struggle for television was written in

December of 1939 in a conference room high above the sidewalks

of Rockefeller Center. A handful of relative strangers were assembled

to finalize the longawaited crosslicense between RCA

and Farnsworth.

Ironically, none of the principals in the story were present.

Neither Sarnoff, Zworykin, nor Farnsworth. Instead, the transaction

was conducted by lawyers for both sides, who had included in the

agreement a historic precedent: after Donald Lippincott, Farnsworth's

longtime patent attorney, authorized the agreement. Otto S. Schairer,

RCA's vice president in charge of patents, sat down to affix his

signature to the first contract that ever required RCA to pay

patent royalties to another company.

Legend has it that Mr. Schairer had tears in his eyes as he signed

the document.

The importance of the occasion was accompanied by very little

fanfare. It passed virtually unnoticed except within the industry.

It is understandable that RCA was not particularly anxious to

publicize the terms of the agreement, lest the industry be given

the impression that RCA was handing out licenses and royalties

for the asking. To the contrary, RCA's capitulation to Farnsworth

strengthened the company's resolve that such a license would never

happen again.

If television was just around the corner-as David Sarnoff started

saying back i n 1936-then the corner turned out to be World War

II, which provided the sort of economic and technical mobilization

necessary to support television on a large scale. Development

of most domestic communications-including television-was suspended

during the war as the electronics industry geared its assembly

lines to produce radar equipment and military communications gear.

When the war ended, those factories converted easily to producing

television receivers, which the commodity starved public was eager

to buy in mounting numbers.

The remainder of Farnsworth's life could fill another volume.

This one ends at the point where the inventor and his first invention

begin to travel separate paths.

While the public became preoccupied with an invention that had

first appeared 20 years earlier, the inventor was now projecting

his own imagination 20 years farther into the future.

Even as the RCA license was being finalized, Farnsworth was drawing

up plans for new lines of research which he first proposed to

the Board of Directors of Farnsworth Television and Radio in

the summer of 1940. The Board rejected his proposals, saying

that the company was too involved in gearing up for mass production

of televisions to devote arty resources toward unrelated research.

Philo sympathized with the Board's point of view, but he could

not go back to fitting all the tubes into a cabinet and reducing

the number of knobs. In the spring of 1940 he packed his jourrials

and retreated to the pastoral isolation of his farm in Maine.

Almost the moment he arrived he started pacing out the foundation

of a laboratory he was going to build adjacent to the house, which

served as his private retreat throughout WWII.

Farnsworth Television and Radio did quite well on defense contracts

during the war, and seemed to be in an excellent position to capitalize

on the market for television receivers that was booming after

the war. But clumsy management caused the company to falter.

Farnsworth returned to Fort Wayne in 1948 in hopes that his presence

might keep the company solvent, but even he was surprised when

he learned the true severity of the company's position.

Ironically, the company lost its footing at just the time that

demand for its principal product was beginning to soar. The company

was sold to International Tele phone and Telegraph in 1949 for

an exchange of stock, and Farnsworth Television and Radio disappeared

from the New York Stock Exchange.

Farnsworth remained in Fort Wayne until 1967, when he resigned from his position

with ITT and moved back to Salt Lake City, where he died in March, 1971.

Farnsworth remained in Fort Wayne until 1967, when he resigned from his position

with ITT and moved back to Salt Lake City, where he died in March, 1971.

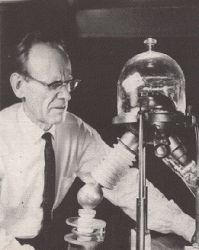

In its obituary on March 12, the New York Times described Philo T.

Farnsworth as as "a reserved, slender, quiet and unassuming man tirelessly

absorbed in his work. At the age of 31 he was rated by competent appraisers

as one of the 10 greatest living mathematicians."

In the course of the past two centuries, many names have been associated

with the inventing of television - Nipkow, Baird, Jenkins, Zworykin, and dozens

of others. None of these names would be remembered today if Philo Farnsworth

hadn't breathed life into the dream that obsessed them all. Recalling Farnsworth's

place in the process provides a point of demarcation between the dream of

sending pictures through the air and the reality that now occupies living

rooms around the world.

Television seemed like a logical extension of all the technological

developments that preceded it. Modern communications began with

the telegraph and the telephone. Radio made it all wireless, and

film made it possible to record images. Television was the longawaited,

much anticipated culmination of these developments. Early

attempts to transmit images tried to use existing technology.

The leap from photomechanical processes to magnetic deflection

and electron scanning, however, was not a matter of mechanics,

but of theory; not a matter of degree but a full order of magnitude.

Farnsworth's direct involvement in the development of television

dropped off after 1940, largely because of his interest in moving

on to higher levels of theoretical research. Nevertheless, he

always kept a watchful eye on his brainchild as it swept across

the nation and the world. Although he was absorbed in his own

work in the 50's and 60's he saw enough of commercial broadcasting

to be disappointed in what he viewed. He felt that the medium's

more constructive applications had been neglected, and wondered

aloud at times if all the energy he spent on television was worth

the effort.

Such uncertainty ended in July, 1969 when Philo and Pem sat in

their living room in Salt Lake City and watched in awe as the

first blurry pictures flickered down to Earth from the surface

of the moon. They smiled knowingly at each other when the near-speechless

Walter Cronkite regained his composure long enough to comment

that, amazing as the lunar landing itself was, even more amazing

was the fact that the entire world witnessed the event on television.

That night, Philo's invention turned one man's lunar stroll into an expression

of global awakening, a moment in which the entire planet became involved in

the unfolding of its own evolution. For Philo Taylor Farnsworth, the event

provided a long-absent moment of personal triumph which erased any doubts

about the value of his contribution. Just seeing with his own eyes that his

invention made it possible for the entire world to witness those historic

steps was enough to make him turn to his wife and say:

That night, Philo's invention turned one man's lunar stroll into an expression

of global awakening, a moment in which the entire planet became involved in

the unfolding of its own evolution. For Philo Taylor Farnsworth, the event

provided a long-absent moment of personal triumph which erased any doubts

about the value of his contribution. Just seeing with his own eyes that his

invention made it possible for the entire world to witness those historic

steps was enough to make him turn to his wife and say:

"This has made it all worthwhile."

The End

While this is the final installment of The Farnsworth Chronicles,

it is hardly the end of the story. It is really only the end of what those of

us familiar with Farnsworth's life like to call "Chapter 1" of an epic that

continues well into the latter half of the 20th century.

After he finished his contributions to television, Farnsworth went on to even more rarified realms of scientific research. Specifically, he spent the 1950's and 60's developing a radical approach to nuclear fusion, the holy grail of modern scientific exploration.

While this is the final installment of The Farnsworth Chronicles,

it is hardly the end of the story. It is really only the end of what those of

us familiar with Farnsworth's life like to call "Chapter 1" of an epic that

continues well into the latter half of the 20th century.

After he finished his contributions to television, Farnsworth went on to even more rarified realms of scientific research. Specifically, he spent the 1950's and 60's developing a radical approach to nuclear fusion, the holy grail of modern scientific exploration.

Based on a phenomenon he observed in his "Multipactor Tube" -- an amplifier tube he developed in the 1930's to boost the weak signal from his Image Dissector tubes -- Farnsworth developed an approach to fusion that -- like his approach to television -- was radical, elegant, and astonishing. The results he produced, as measured by something called "neutron counts," far exceeded anything that any other researchers in the field have ever come close to. Unfortunately, his approach was SO radical that funding was hard to come by, and Farnsworth took the secrets to his grave when he died in 1971.

Click here to read more

about "Chapter 2" in the Life of Philo T. Farnsworth

If you would like to share any comments about this story

with its author, please follow this link to the

guestbook. If you would like to share your thoughts in a public forum,

follow this link to the Philo Message Center.

Finally, those of you who would like to learn more about Farnsworth should

consider obtaining a copy of Pem Farnsworth's biography Distant

Vision: Romance and Discovery on the Invisible Frontier. The book

can be ordered directly from the

Official Philo T. Farnsworth Archives website

There are a number of supplemental installments

you might also like to read:

Restoring Philo's Place In History

-- 0bserving the 50th Anniversary of the First Video Transmission

TeeVee Honors Its Patron

Saint

Farnsworth's appearance on the 1950s TV game show, "I've

Got a Secret"

"Who

Invented What and When"

a detailed assessment of the historical record of the origins of

electronic television

This story is brought to you

as a public service by:

| 49chevy.com |

� 1977, 2001Paul Schatzkin; All Rights Reserved

For more information contact: The Perfesser

|