Part 9: "You're All Fired!"

by Paul Schatzkin

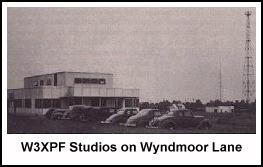

Philo T. Farnsworth and his partner, Russel Seymour "Skee" Turner, decided to go ahead with their plans to build a television studio separate from the laboratories at Mermaid

Lane, regardless of the response of Farnsworth's other backers. Skee Turner felt so strongly that such a facility was essential if Farnsworth was ever to surmount the day-to-day problems of commercial television, that he put up enough money himself to

erect a prefabricated structure on a hill in the Wyndmoor section of Philadelphia.

While the empty building was fitted with a stage and lights, Farnsworth and

the lab gang devoted their time to building two state-of-the-art Image Dissector

cameras. These cameras were built for durability as well as high resolution.

All the equipment was engineered so that camera and picture tube would both

be capable of producing 441 lines per frame - well in excess of the 400 lines

per frame that Farnsworth had established as his objective back in 1928.

While the empty building was fitted with a stage and lights, Farnsworth and

the lab gang devoted their time to building two state-of-the-art Image Dissector

cameras. These cameras were built for durability as well as high resolution.

All the equipment was engineered so that camera and picture tube would both

be capable of producing 441 lines per frame - well in excess of the 400 lines

per frame that Farnsworth had established as his objective back in 1928.

Farnsworth's crew created and built a special transmitter and

a 100-foot tower that could blanket the Philadelphia metropolitan

area with experimental television signals. They also designed

and built the world's first electronic video switcher, which allowed

instantaneous intercutting between the two cameras as programs

were broadcast. While all the equipment was under construction,

the FCC granted Farnsworth a license to conduct experimental television

transmissions under the call letters W3XPF.

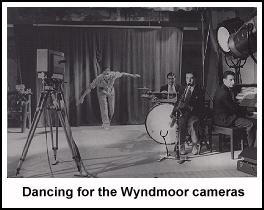

One big job for the new broadcasters was finding artists to perform

before the electronic eye. Farnsworth had learned during the Franklin

Institute public demonstration in 1934, that he could rely on

an endless supply of amateur singers, dancers, musicians and magicians

willing to trade their time for a little exposure and the undeniable

thrill of being televised.

What programs they were able to assemble were broadcast to a handful of receivers

that were beginning to appear around Philadelphia. By now there were three

companies in the area experimenting with electronic television: Farnsworth,

RCA and Philco. Many of the engineers who worked for these companies had receivers

in their homes that they used to monitor transmissions from their laboratories.

The few dozen homes that were actually equipped with TV became focal points

of the neighborhood, truly the first on their block.

What programs they were able to assemble were broadcast to a handful of receivers

that were beginning to appear around Philadelphia. By now there were three

companies in the area experimenting with electronic television: Farnsworth,

RCA and Philco. Many of the engineers who worked for these companies had receivers

in their homes that they used to monitor transmissions from their laboratories.

The few dozen homes that were actually equipped with TV became focal points

of the neighborhood, truly the first on their block.

For the time being at least, television was getting started in

much the same way as radio, in the hands of a few clever enthusiasts

who could build their own receivers to catch whatever was in the

air.

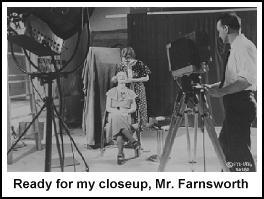

Some amusing peculiarities were discovered in the Image Dissector

tube as it began the routine of transmitting television programs

on a daily basis. The characteristics that caused the most headaches

arose from the tube's unusual infrared sensitivity, which caused

red, which normally photographs black, to televise as white.

The Max Factor Company in Hollywood contributed their expertise in early color

movies, and the coloration problems were solved by applying blue makeup around

the lips and eyes. Consequently, performers who appeared perfectly normal

on the TV monitor looked ghoulishly blue to the unaided eye.

The Max Factor Company in Hollywood contributed their expertise in early color

movies, and the coloration problems were solved by applying blue makeup around

the lips and eyes. Consequently, performers who appeared perfectly normal

on the TV monitor looked ghoulishly blue to the unaided eye.

The Image Dissector also displayed a peculiar sensitivity to certain

fabrics which rendered them transparent, as was graphically illustrated

the day a pretty ballerina appeared to be dancing naked on the

video screen.

Video broadcasts from the Farnsworth studios not only proved the

feasibility of television, they gave Farnsworth a public image,

and the boy genius from Utah became a minor celebrity. Though

fewer than 50 homes in the Philadelphia area were equipped with

video receivers, the activity was enough to add the word "television"

to the language.

For a few months, Farnsworth enjoyed the attention; it was a welcome

change after nearly 10 years of hard work in total obscurity.

But eventually the obligations of even minor celebrity status

became too pressing a burden on his time. What with meetings and

interviews and visits from foreign dignitaries all hoping to spend

a few minutes with the great Farnsworth, being famous became a

job in itself, entirely apart from the work that made him famous

in the first place.

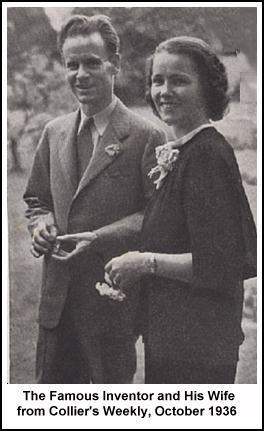

The flood of publicity peaked in 1936 when the Paramount Newsreel

Service, the Eyes and Ears of the World, ran two stories about

the coming of television and the remarkable man who put it all

together. One story described Farnsworth as the man who made "mankind's

most fanciful dream about to become a startling reality."

By raising the visibility of the company, nationwide publicity raised the

value of the stock, and the value of everybody's holdings swelled appreciably.

Some accountant with a sardonic wit told Farnsworth that at current prices,

his own holdings were worth more than $1,000,000-these figures made Farnsworth

a living example of the American dream-a millionaire before his 30th birthday.

Of course, this was only a "paper" fortune. The fact was, Jess and

George McCargar continued having difficulty finding investors willing to buy

into a company that could not sell its only product.

By raising the visibility of the company, nationwide publicity raised the

value of the stock, and the value of everybody's holdings swelled appreciably.

Some accountant with a sardonic wit told Farnsworth that at current prices,

his own holdings were worth more than $1,000,000-these figures made Farnsworth

a living example of the American dream-a millionaire before his 30th birthday.

Of course, this was only a "paper" fortune. The fact was, Jess and

George McCargar continued having difficulty finding investors willing to buy

into a company that could not sell its only product.

In October 1936, Colliers Magazine ran a feature story about "Phil

the Inventor," that said that television seemed destined

to find its way into many American homes by Christmas, 1937. This

prediction reflected a common feeling of the time, that commercial

television was "just around the corner." But Farnsworth

knew that as long as his patents remained under contention, turning

corners would have to wait for another day.

One Step Into the Future

With the job of perfecting and promoting electronic television

off to a strong start under its own roof, life at Farnsworth's

Mermaid Lane Laboratory took on a new dimension. The smell of

new work permeated the air as Farnsworth and his loyal "lab

gang" began to look back on what 10 years of refining television

had taught them.

Many of the men still working for Farnsworth had joined him years

earlier in San Francisco. Under Farnsworth's youthful guidance,

this unlikely group managed to turn the tangle of wire and glass

that produced the first electronic television picture into the

total fulfillment of "mankind's most fanciful dream."

Others before them had failed, crying that it could not be done

without massive infusions of capital, but Farnsworth and his lab

gang proved them all wrong. They not only invented TV, they overcame

the limitations of their financing and delivered their invention

to the marketplace, ready for the start of commercial broadcasting.

After so many successful years together, the lab gang began to

take on the air of scientific invincibility. The unwritten motto

for the entire operation was: "The difficult we do right

away. The impossible takes slightly longer."

In 1935, Farnsworth's attorney, Donald K. Lippincott, filed applications

for 32 new patents which covered improvements in television as

well as some new work that was not directly related. Farnsworth

was proud of these submissions because some of them embodied original

discoveries he made over the years. But what excited him most

about this batch of patents was that 14 of them were attributed

to members of the lab gang other than Farnsworth himself.

This score reflects the collective spirit that Farnsworth instilled

in his coworkers. This straightforward approach to his work provided

an incentive that tied the lab gang together. Their hours were

long, the work was sometimes tediously painstaking, and the pay

was never abundant, but Farnsworth never had any trouble finding

capable men who were not only willing but eager to work with him.

As the lab gang grew, Farnsworth chose new men very carefully, watching closely

for people who displayed both compatibility and trainability. Admission to

the lab gang was predicated primarily on an applicant's willingness to take

chances. What kept the lab going was men who could, by following Farnsworth's

example, find their own way of doing whatever they'd been assigned, and make

it work. In this manner, Farnsworth built a well organized team that could

deliver the specific ingredients of his designs.

As the lab gang grew, Farnsworth chose new men very carefully, watching closely

for people who displayed both compatibility and trainability. Admission to

the lab gang was predicated primarily on an applicant's willingness to take

chances. What kept the lab going was men who could, by following Farnsworth's

example, find their own way of doing whatever they'd been assigned, and make

it work. In this manner, Farnsworth built a well organized team that could

deliver the specific ingredients of his designs.

"I'm building men, not gadgets," Philo once said, and

the extraordinary results of his unique style of work and leadership

was a testimony to that philosophy.

Once accepted, a new employee found himself welcomed into what

Tobe Rutherford called, "one big happy family." Indeed,

many lab workers were members of his immediate family: his brothers

Carl and Lincoln were both members of the lab gang. His sister,

Laura studied with Max Factor, and became the resident make-up

consultant. And his chief tube-builder was his brother-in-law.

This extended family became a collective unit that was the extension

of Philo's incredibly creative scientific mind.

At the same time that he was directing members of his research

team to solve particular problems that grew out of the day to

day television operations, Philo concentrated his own attention

on dozens of problems in basic science which his instincts led

him to explore. It was the solid back up of his laboratory group

which provided the support necessary for him to begin explorations

in the outer stratosphere of physics.

Farnsworth became convinced that there was no limit to the things

he could get electrons to do in a vacuum bottle. He turned to

his lab gang to construct the tubes and circuits that could prove

his point. Electronic television, which began as a dream in the

mind of a child, was now a virtual reality, but the lab gang was

the fulfillment of an even grander dream. Television was as much

the product of their sweat as it was the gift of his genius. Farnsworth

was the dreamer, and the lab gang was the instrument of his dreams.

With these men at his side, whatever Farnsworth wished of the

future was at his command.

Throughout 1935 and 1936, Farnsworth carried a considerable work

load. He spent long mornings at the studio, personally demonstrating

his invention for the daily tide of visiting dignitaries and scientists

who felt they were entitled to a few minutes of Farnsworth's time.

The afternoons he spent at the laboratory on Mermaid Lane, working

on solutions to problems that came up at the studio. The evenings

he spent either at the lab or at home, working on his new ideas

and developing the mathematics for his own theories.

These jobs alone were enough for three men, but there was no end

to the distractions that kept Farnsworth away from what he considered

the important work. Most disturbingly, the people who were primarily

responsible for funding Farnsworth's enterprise did not share

his enthusiasm for opening new lines of research. After all, there

was still no settlement in sight from RCA, and the dream of video

broadcasting remained indefinitely postponed. Until the RCA litigation

was cleared up, all this talk of advanced science struck Jess

McCargar as somewhat premature.

In fact, McCargar was beginning to display impatience with the

whole affair, and suggested on more than one occasion that maybe

accepting RCA's offer for a complete sell out wasn't such a bad

idea after all. The suggestion only proved to Phil that Jess would

never understand how a patent was something that could earn money

from licensing, without ever being sold. McCargar could only make

judgments based on how much things cost, and now, as usual, they

cost too much.

Farnsworth to the Rescue

In the closing months of 1936, these pressures began to exercise

a noticeable effect on Farnsworth's delicate physiological balance.

He began to show the signs of growing tired each day, and his

disposition sometimes turned sour. After pushing himself relentlessly

for 10 years, he was finally beginning to reach the limits of

his endurance.

As if life on Mermaid Lane wasn't already intense enough, Farnsworth

learned in the autumn of 1936 that his only licensee, Baird of

England, was in trouble. The BBC was all set to award its television

contract to EMI, but Baird and his backers raised such a fuss

that the matter came up in Parliament, where the Selsdun Committee

was appointed to make certain that the BBC conducted competitive

testing between EMI and Baird before awarding the contract. As

the tests got underway in 1936, Baird started having problems

with his Image Dissector tubes. He couldn't get a picture.

Unfortunately for Farnsworth, there was no one else in the world

Baird could turn to for help. Aside from being tired, he was understandably

reluctant to leave the lab. But since his only industrial ally

was on the verge of collapse, he had no choice. He agreed to go,

with two stipulations: he insisted on taking a slow boat, so that

he could have a few days to rest; and he insisted that passage

be provided for his wife Pem. Baird accepted these conditions,

and Mr. and Mrs. Farnsworth sailed for Europe, making a honeymoon

of it 10 years after their wedding.

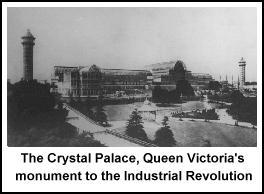

In London, Farnsworth found Baird's equipment set up in the elegant Crystal

Palace in Kensington Gardens, the remarkable glass and steel edifice that

Queen Victoria had built in the 19th century to house an industrial exhibition.

Farnsworth was shocked to discover the real source of Baird's problems: two

years after taking a license from Farnsworth, Baird was still using the scanning

disc for certain components of his system. True, Baird had pushed his mechanical

creation to the point that it could deliver some 200 lines per frame, but

the competing system offered by EMI produced 405 lines per frame, and clearly

left Baird standing in the cold.

In London, Farnsworth found Baird's equipment set up in the elegant Crystal

Palace in Kensington Gardens, the remarkable glass and steel edifice that

Queen Victoria had built in the 19th century to house an industrial exhibition.

Farnsworth was shocked to discover the real source of Baird's problems: two

years after taking a license from Farnsworth, Baird was still using the scanning

disc for certain components of his system. True, Baird had pushed his mechanical

creation to the point that it could deliver some 200 lines per frame, but

the competing system offered by EMI produced 405 lines per frame, and clearly

left Baird standing in the cold.

Baird was using his Image Dissector tube for his "cinefilm"

transmitter, which is the British euphemism for a film-chain,

but even in this capacity he was not taking full advantage of

the Dissector's capacities. In fact, Farnsworth found the chassis

for the Dissector only partially built; Baird and his men simply

didn't know how to finish it.

Once he was on the scene at the Crystal Palace, Farnsworth plunged

into an around-the-clock schedule to put Baird back in business.

When he was done, Farnsworth and his wife drove with Baird and

members of the Selsdun Committee to a small pub outside London

where a cathode ray tube receiver was set up to catch Baird's

over-the-air transmission. Everybody saw the crisp detail and

subtle contrasts in the picture delivered by the Farnsworth Image

Dissector.

Still, there was really little Philo T. Farnsworth could do to

help John Logie Baird as long as the Englishman hung onto his

spinning discs. Evidently, British Gaumont, Baird's backers, felt

pretty much the same way as Farnsworth. It seemed that Baird's

chances of winning the BBC contract were doomed even before Farnsworth

arrived at the Crystal Palace.

Having done all that he could for Baird, Farnsworth disappeared

with his wife for three weeks on the French Riviera. Conversation

during their train ride across France centered on the recently

exposed intrigue of Edward VIII's illicit romance. The Farnsworths

arrived on the Riviera at almost the same time as Wallace Simpson,

the object of Edward's affections, who was forced to flee London

as word of her relationship with the King leaked out.

Phil and Pem spent three well-deserved weeks on the beach, during which time

Edward announced his abdication. Those three quiet weeks provided a much needed

period of rest for both Phil and Pem, their first real vacation after more

than 10 years of hard work. It was also the first opportunity that Phil and

Pem had in as many years to spend a period of time alone together. The backdrop

of the French Riviera provided just the right romantic touch to reawaken the

fire of their affection.

Phil and Pem spent three well-deserved weeks on the beach, during which time

Edward announced his abdication. Those three quiet weeks provided a much needed

period of rest for both Phil and Pem, their first real vacation after more

than 10 years of hard work. It was also the first opportunity that Phil and

Pem had in as many years to spend a period of time alone together. The backdrop

of the French Riviera provided just the right romantic touch to reawaken the

fire of their affection.

While they were on the Riviera, the Farnsworths were shocked to

read one morning that the Crystal Palace was leveled by a fire

of mysterious origins, which destroyed all of John Logie Baird's

equipment, including Farnsworth's Image Dissector. The fire brought

almost total ruination to John Logie Baird, and all but guaranteed

that EMI would win the contract to put BBC into electronic television.

The news was a set back to the energy that this trip seemed to

be gathering. Before sailing home, Phil and Pem made one more

stop in London to survey the damage. Sifting through the rubble

of the Crystal Palace, Phil found a macabre souvenir of the tragedy-the

charred, melted remains of his Image Dissector tube, which he

carefully placed in one of his bags, to be carried home with him

as a grim reminder of what was left of the British hope.

The Beginning of the End

After six weeks absence Philo looked forward anxiously to returning

to his laboratory to see what had become of the patents that were

filed prior to his departure. He had left the work in capable

hands before he left, and hoped to see that some interesting results

had been produced while he was away.

Instead of hopeful signs of progress, Farnsworth was dismayed

to discover that some of the patents that seemed most valuable

had been abandoned while he was away only because they had no

direct applications to TV. But more importantly, Farnsworth discovered

discontent coming from everybody in the lab over the way that

things had been handled during his absence.

Phil learned that Jess McCargar had sent Russ Pond, one of his

buddies in the stock-peddling business to Philadelphia to take

over the management of the lab. Pond was cut from the same fabric

as McCargar, and had no prior experience with anything that involved

electronics or engineering. Nevertheless, he took his role very

seriously, but showed little regard for the delicacies of science.

The result of his arbitrary management was a badly demoralized

lab gang. Farnsworth found everybody grumbling about how things

had fallen apart in the six short weeks while he was in Europe.

The entire lab gang was suffering from a case of badly damaged

esprit de corps.

Russ Pond was sent back to San Francisco immediately, but it was

too late to prevent the rapid chain of events that would lead

to a confrontation with Jess McCargar. That encounter became inevitable

when Jess decided that Phil should reduce the payroll by dismissing

some of his staff, and then decided to come East to deliver the

ultimatum to Farnsworth in person.

This, Farnsworth decided, was the place to plant his feet. We

would not allow McCargar's shortsightedness to jeopardize his

most valuable asset. Every one of his men performed some essential

role and none could be spared without affecting numerous phases

of the total operation. Nor could he face the emotional stress

of deciding who should go and who should stay. It would have been

too much like choosing between his children.

McCargar was adamant. "Well," he scowled, "If you

can't fire some of them, fire all of them, and hire back the ones

you need."

Farnsworth refused to fire a single man, so Jess McCargar took

matters into his own hands, as if to show Farnsworth who was really

the boss. McCargar stormed defiantly out of Phil's office and

announced to everyone present with gloomy finality,"You're

all fired."

Farnsworth sat alone in his office while his men filed out, quiet

and perplexed. Waves of anger and despair seized him as he tried

to assess what McCargar had done to his life. The spirit left

the room when Farnsworth walked out of the lab alone that night.

Pem already knew what had happened when Phil walked in the house,

looking beaten and depressed. She tried to talk about it but Phil

was still too overwhelmed and confused to articulate his feelings.

They went to a movie instead.

Later that evening, Phil called some of the men to see if they

would come back, but every call met the same response. Even Tobe

Rutherford had taken all the static and interference he could

from Jess McCargar and refused. He just didn't have the stomach

for it as long as Jess McCargar remained in charge.

Hard as it was for Tobe and the others, it was even harder for

Phil. As the full impact of McCargar's blind ruthlessness became

apparent, Farnsworth realized that the foundation of his future

lay in ruins, and felt that all of his struggles had been in

vain. It seemed senseless to continue to stand up in the face

of external threats if he was only going to be knocked down in

the end by the people who were supposed to be on his side.

End of Part 9

Continue with:

Part 10: "Caught In

The Crossfire"

This story is brought to you

as a public service by:

| 49chevy.com |

� 1977, 2001Paul Schatzkin; All Rights Reserved

For more information contact: The Perfesser

|